Comment

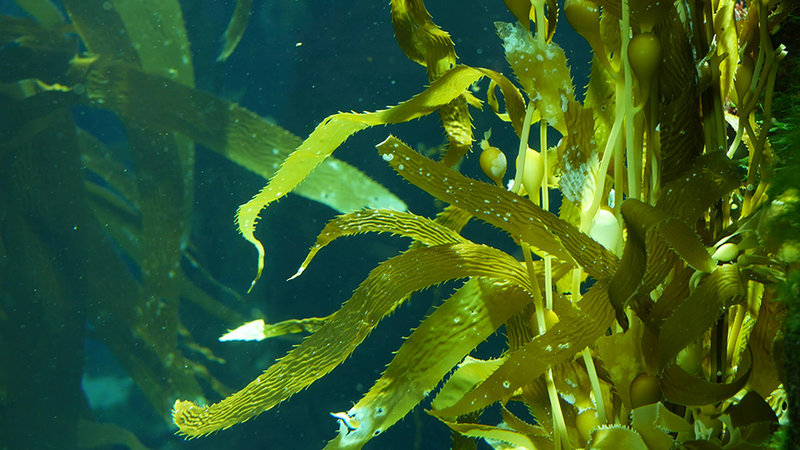

The growing potential of seaweed fibres

The need for alternative materials to paper and cardboard is becoming increasingly apparent. At the height of the first lockdown in 2020, the UK experienced a cardboard shortage, caused by a spike in online sales by consumers who’d been told to stay at home.

Supply chains temporarily struggled to catch up with the behavioural change accelerated by the pandemic. Even now, cardboard shortages are still with us as businesses make greater efforts to avoid plastic to meet growing consumer demands for sustainability.

At the same time, wildfires sweeping through paper and card’s source material have become a more common occurrence. And, while politicians pledge to intensify tree planting to offset carbon emissions, trees are hardly going to take CO2 out of the air if they are turned to ash.

An alternative solution is out there, for a global economy that has become dependent on cardboard - seaweed. For a start, there’s no risk from fire. And, at a growth rate of six inches a day in the right conditions, seaweed grows is faster than any tree.

The crop is also self-sustaining and needs next to no maintenance. Seaweed gets everything it needs from seawater, without requiring any watering, fertilising or weeding. Furthermore, there are barely any diseases that could kill the crop or restrict growth.

Now, packaging manufacturer DS Smith is undertaking research into how fibres from seaweed can be used as a more environmentally-friendly way of making paper and cardboard.

Greener paper

While paper and cardboard are among the more eco-friendly packaging materials - and are easily recycled - this doesn’t mean they’re without any environmental impact: An estimated 55% of all global paper still comes from cutting down trees. Cardboard is also sometimes incorrectly sent to landfill sites, releasing methane as it breaks down.

Yet, there are promising signs that using seaweed to make sustainable paper for packaging uses less energy and lower amounts of chemicals. Packaging made from seaweed may also be easier to recycle.

DS Smith is focussing its research on three different types of seaweed - brown, green and red. The company hopes to determine which variety shows the most promise for packaging alternatives.

“Seaweed has the potential to be a sustainable fibre and raw material source with a low ecological footprint that is easily recyclable and naturally biodegradable,” explains DS Smith’s paper and board development director, Thomas Ferge. “It also has the potential to be less energy-intensive in the production process, with fewer chemicals used to extract the fibres. We’re carrying out tests to better understand these factors, in combination with fibre yield and resulting product properties to enable our performance-based circular design principles.”

At present, however, there is no time frame for when packaging materials made from seaweed could be commonly available.

“We’re not in a position to give a firm timeline yet,” Ferge admits.”Our research and tests will help us drive this project forward and answer questions around seaweed’s strength, resilience and recyclability and its use as a base material for barrier coatings to replace plastics and potentially as a fibre source for paper.

“Critically, our work here is backed by a firm budget commitment and is part of a wider GBP100m (US$138m) R&D programme to boost our research on alternative fibres.”

DS Smith has set a target of manufacturing fully reusable or recyclable packaging by 2023. By 2030, the company’s aim is for all of its packaging to be either recycled or reused. The group, which has annual sales of just over GBP6bn, is also working with governments to improve recycling rates and has been taking the lead on packaging such as disposable coffee cups.

As part of the R&D programme, the company is also researching fibres from other materials to determine their potential uses in packaging. Materials being tested include straw, hemp, cotton and cocoa shells.

“We’re looking into multiple alternative fibres as part of the R&D programme,” says Ferge. “At this stage, we cannot confirm how the fibres compare with each other, but are actively researching their qualities including resilience, recyclable properties, scalability and cost.”

The case for seaweed

Seaweed is highly effective at sequestering carbon dioxide. The world’s seaweeds are thought to consume as much as 200m tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, the equivalent of New York City’s annual CO2 production. Furthermore, there are estimates that coastal marine systems can absorb up to 50 times more carbon than land-based forests.

When seaweed dies, currents often carry it to the ocean depths, also taking much of the carbon consumed in its lifetime. Harvested seaweed is also far lighter to transport than felled trees.

Using seaweed to make paper is not a new development. A study by the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur used red seaweed to make paper. Researchers found the process to have a significantly lower environmental impact than traditional methods for creating wood pulp.

To make pulp for paper, wood is required. The material needs to be cooked for eight hours at temperatures of 180°C. In comparison, University of Malaya researchers used red seaweed to make pulp with a cooking time of two hours at 100°C. This is a significant energy saving.

Paper also needs to go through seven stages of bleaching to remove coloured compounds. Whereas with seaweed pulp, only two stages of bleaching are required.

The presence of seaweed in our everyday lives looks set to increase in the years ahead. The seaweed market is expected to expand rapidly within the next decade. In Europe, the market is projected to have a value of GBP8bn, creating an estimated 115,000 jobs.

How green will the future be? If seaweed has its way, then very.

Seaweed has emerged as the unexpected hero in the fight against climate change. Projects already underway include using the marine crop from everything from biofuels and plastic replacements to reducing methane emissions from cows. And now, paper and cardboard could be the next way that the humble seaweed changes the world. Alex Love investigates.